This week on the Strangely Warmed podcast I speak with Alan Combs about the readings for the Fifth Sunday of Lent [C] (Isaiah 43.16-21, Psalm 126, Philippians 3.4b-14, John 12.1-8). Alan is the lead pastor of First UMC in Salem, VA. Our conversation covers a range of topics including record breakers, timelessness, keeping Easter in Lent, Makoto Fujimura, laughing in church, terrible testimonies, tremendous transformation, clarity (or the lack thereof), authorial soliloquies, and John Daker. If you would like to listen to the episode or subscribe to the podcast you can do so here: Narding Out

Tag Archives: Preaching

Welcome Home

Luke 15.1-3, 11b

Now all the tax collectors and sinners were coming near to listen to him. And the Pharisees and the scribes were grumbling and saying, “This fellow welcomes sinners and eats with them.” So he told them this parable: “There was a man who had two sons…”

The strange new world of the Bible is downright scandalous.

I mean, the first two human characters in it, Adam and Eve, spend most of their time in their birthdays suits before they decide to cover themselves with a handful of fig leaves.

The patriarch of the covenant, Abraham, passes off his wife as his sister on more than one occasion to save his own behind.

David, the handsome shepherd king who brings down the mighty Goliath, orders the death of one of his soldiers after an afternoon peeping session with the aforementioned solider’s wife.

And those are just the first three stories that popped in my mine.

When Jesus shows up on the scene, the scandalous nature of the Good News ramps up to eleven.

He eats with all the wrong people, he heals all the wrong people, and he makes promises to all the wrong people.

In the beginning, Jesus attracts all kids of people. The good and the bad, the rich and the poor, the holy and the sinful, the first and the last.

But at some point along the way things start to change as do the people who find themselves listening to Jesus.

All the tax collectors and all the sinners come near to listen. The tax collectors are those who profit off their fellow Jews by upping their take for the empire’s pockets. And the sinners, well you can just imagine your favorite sinful behavior, and you can picture them near the Lord.

And so it is the last, least, lost, little, and nearly dead who hang on his every word. Not the respectable Sunday morning crowd we have at church. Not those who sleep comfortably at night knowing their padded bank accounts are safe and secure. Not the people who have all the powers and principalities at their fingertips.

No. Jesus has all the gall to hang out with the sinners.

And the Pharisees, the good religious observers (people like us), are concerned about the behavior of this would-be Messiah, and so they try to dissuade the crowds: “This Jesus is nothing but bad news! He welcomes sinners into his midst, and not only that, he eats with them! Can you imagine? And he calls himself the Son of God!”

So Jesus does what Jesus does best, he tells them a story.

There’s a man with two sons. The family business has been good to the family. The little corner grocery store is a staple in the community and the family know the names of just about every person that walks through the door.

And the father is a good father. He loves his sons.

But one day the younger son gets it into his head that he wants his inheritance right then and there. He doesn’t have the patience to wait for his old man to buy the farm so he marches into the back office and triumphantly declares, “Dad, I want my share of the inheritance now.”

In other words, “Drop dead.”

And the father really is a good father, so he decides to divide his assets between his sons. To the elder he gives the property and the responsibility of the family business, and to the younger he cashes out some investments and gives him his half in cold hard cash.

Only a few days pass before the younger son blows all of his money in Atlantic City. At first he is careful, a few passes at the roulette wheel, a handful of bets at black jack. But the more he loses, the more he spends on booze, girls, and more gambling,

His fall from grace happens so fast that he walks up to the closest pit boss with empty pockets and begs for a job.

“Sure,” the man says, “we’ve got an opening in janitorial services and you can start right now.”

Days pass and the younger son cleans out the trashcans throughout the casino. He’s able to stave off the hunger at first, but he hasn’t eaten in days and one particular half-consumed doughnut at the bottom of the trash can starts to look remarkably appetizing.

And that’s when he comes to himself.

He realizes, there in that moment, that he made a tremendous mistake. Even the employees back at the family grocery store have food to eat and roofs over their heads.

He drops his janitorial supplies and beelines out of the casino while working on a speech in his head, “Dad, I really messed up. I am sorry and I am no longer worthy to be called you son. If you can give me a job at the store I promise I’ll make it up to you.”

He says the words over and over again in his head the whole way home, practicing the lines like his life depends on them.

Meanwhile, the father is sitting by the window at the front of the shop, lazily glancing over the newspaper’s depressing headlines. He can hear his elder son barking out orders to his former employees, and then he sees the silhouette of his younger son walking up the street.

He sprints out the front door, spilling his coffee and leaving a flying newspaper in his wake. He tackles his son to the ground, squeezes him like his life depends on it, and he keeps kissing him all over his matted hair.

“Dad,” the son says, “Dad, I’m sorry.”

“Shut up boy,” the father roars, “We’re gonna close the shop for the rest of the day and throw a party the likes of which this neighborhood has never seen!”

He yanks his prodigal son up from the asphalt, drags him back up the block, and pushes him in front of everyone in store.

“Murph,” he yells at a man with a broom standing at the end of an aisle, “Lock the front door and go find the nicest rack of lamb we’ve got. We’ll start roasting it on the grill out back.”

“Hey Janine!” He yells at a woman behind the cash register, “Get on the PA system and call everyone to the front, and open up some beers while you’re at it. It’s time to party! This son of mine was dead and is alive again, he was lost and now is found!”

And the beer caps start flying, and the radio in the corner gets turned up to eleven, and everyone starts celebrating in the middle of the afternoon.

Meanwhile, the older son is sitting in the back office pouring over the inventory and comparing figures to make sure that none of his employees are swindling him out of his money, and he hears a commotion going on down the hallway. He sees Murph run past the door with what looks like beer foam in his mustache, and what looks like a leg of lamb under his arm, and the elder son shouts, “What in the world is going on?”

Murph skids to a stop in the hallway and declares, “It’s your brother, he’s home! And your father told us to party!” And with that he disappears around the corner to get the grill going.

The older brother’s fists tighten and he retreats back to his office chair and to his ledger books.

Try as he might he can’t focus on his work. All he can think about is his good for nothing brother and all of the frivolity going on mere feet away. His anger grows so rapidly that he grabs the closest stack of papers and flings them across the room.

And then he hears a knock at the door.

His father steps across the threshold, clearly in the early stages of inebriation. He mumbles, “Hey, what’re you doing back here? You’re missing all the fun!”

The older son is incredulous. “What do you mean, ‘What am I doing back here?’ I’m doing my job! I’ve never missed a day of work, I’ve been working like a slave for you and you never once threw me a party, you never told me I could go home early. And yet this prodigal son of yours has the nerve to come home, having wasted all your money with gambling and prostitutes, and you’re roasting him a leg of lamb!”

The father sobers up quickly, and maybe it’s the beer or maybe it’s is own frustration, that causes him to raise his voice toward his eldest son, “You big dumb idiot! I gave you all of this. You haven’t been working for me, you’ve only been working for yourself. Last time I checked, it’s your name on the back of the door, not mine.”

The elder son stands in shock.

And the father continues, “Remember when your brother told me to give him the inheritance? Well I trusted you with this, the family business. And what does your life have to show for it? You’re so consumed by numbers and figures, and doing what you think you’re supposed to do, all the while you’re chasing some bizarre fantasy of a life that doesn’t exist.”

“But Dad…”

“Don’t you, ‘But Dad’ me right now, I’m on a roll. Listen! All that matters, the only thing that matters, is that your brother is finally alive again. But look at you! You’re hardly alive at all. There’s a party going on just down the hall and you can’t even bring yourself to have a good time. Well, remember son of mine, complain all you want, but don’t forget that you’re the one who owns this place.”

The father makes to leave and rejoin the party, but he turns back one last time toward his elder son and says, “I think the only reason you’re not out there cutting up a rug with the rest of us is because you refuse to die to all your dumb rules about how your life is supposed to go. So, please, do yourself a favor, and drop dead. Forget about your life, and come have fun with us.”

The End.

And, of course, we know what we’re supposed to do with the story.

At times we’re supposed to identify with the younger brother, having ventured off toward a handful of mistakes, and we need to repent of our wrong doings.

At times we supposed to identify with the father, with our own wayward child, or friend, or partner, and how we have to pray for them to come to their senses and receive them in love.

At times we’re supposed to identify with the elder brother, when we’re disgusted with how some people get all the good stuff even though their rotten.

And just about every time we encounter this parable, whether in worship, Sunday school, or even a book or movie, the same point is made – find yourself in the story and act accordingly.

But that ruins the story. It ruins the story because it makes the entire thing about us when the entire thing is actually about Jesus.

If it were about us it would certainly have a better ending. We would find out from the Lord whether or not the elder brother decides to join the party, if the younger brother really kept to the straightened arrow, and if the father was able to get his sons to reconcile with one another.

But Jesus doesn’t give us the ending we want. We don’t get an ending because that’s not the point.

The point is rather scandalous – no one gets what they deserve and the people who don’t deserve anything get everything!

In Jesus’ parable we encounter the great scandal of the gospel: Jesus dies and is resurrected for us whether we deserve it or not. Like the younger son, we don’t even have to apologize before our heavenly Father is tackling us in the streets of life with love. Like the older son, we don’t have to do anything to earn an invitation to the party, save for ditching our self-righteousness.

Contrary to how we might often imagine it, the whole ministry of the Lord isn’t about the importance of our religious observances, or our spiritual proclivities, or even our bumbling moral claims. It’s about God have a good time and just dying, literally, to share it with us.

That’s what grace is all about. It is the cosmic bash, the great celebration, that constantly hounds all the non-celebrants in the world. It begs the prodigals to come out and dance, and it begs the elder brothers to take their fingers out of their ears. The fatted calf is sacrificed so that the party can begin. Jesus has already mounted the hard wood of the cross so that we can let our hair down, take off our shoes, and start dancing.

We were lost and we’ve been found. Welcome home. Amen.

Don’t Be A Jerk

This week on the Strangely Warmed podcast I speak with Wayne Dickert about the readings for the Fourth Sunday of Lent [C] (Joshua 5.9-12, Psalm 32, 2 Corinthians 5.16-21, Luke 15.1-3, 11b-32). Wayner is the pastor of Bryson City UMC in Bryson City, NC. Our conversation covers a range of topics including fresh expressions, summer internships, stones, dis-grace, mighty waters, praying by listening, new creations, ambassadors for Christ, prodigals, and Robert Farrar Capon. If you would like to listen to the episode or subscribe to the podcast you can do so here: Don’t Be A Jerk

Holy Fertilizer

Luke 13.1-9

At that very time there were some present who told him about the Galileans whose blood Pilate had mingled with their sacrifices. He asked them, “Do you think that because these Galileans suffered in this way they were worse sinners than all other Galileans? No, I tell you; but unless you repent, you will all perish as they did. Or those eighteen who were killed when the tower of Siloam fell on them – do you think that they were worse offenders than all the others living in Jerusalem? No, I tell you; but unless you repent, you will all perish just as they did.” Then he told this parable: “A man had a fig tree planted in his vineyard; and he came looking for fruit on it and found none. So he said to the gardener, ‘See here! For three years I have come looking for fruit on this fig tree, and still I find none. Cut it down! Why should it be wasting the soil?’ He replied, ‘Sir, let it alone for one more year, until I dig around it and put manure on it. If it bears fruit next year, well and good; but if not, you can cut it down.’”

Interior coffee shop: early morning.

Rain falls steadily against a window.

An assortment of customers in various states of caffeination are spread out among the tables and chairs.

A preacher sits alone in the corner. Computer and Bible are on the table, a subpar sermon is coming along splendidly.

He tries to focus on the matter at hand, but he can’t help but overhear a conversation from a nearby table.

“Can you believe he cheated on her?”

“Oh honey, that’s not the half of it. I heard he’s been living two lives between two houses with two different families.”

The preacher knows better than to eavesdrop, so he goes back to the flashing cursor on his computer. He’s able to jot a few ideas down, none of which will actually make it into the sermon. When, a few minutes later, he catches bits of different conversation at a different table.

“You know, the Ukrainians, they’re getting what they deserve. They elected that Zelensky and his liberal agenda. I think we would do well to have a leader like Putin here, someone tough who isn’t going to let anything get in his way.”

The preacher closes his computer and decides to leave before he overhears even more sinners talking about other sinners and their sin.

There are times when I like to think that we’ve come a long way since the time of our Lord, that we’ve progressed from some of our wandering recklessness.

And then I am reminded that, all things considered, not much has changed.

Do you think those Galileans suffered because they were worse sinners than other Galileans? No, I tell you; but unless you repent, you will die like them.

What a grace-filled and hopeful word from the Word!

Robert Farrar Capon wrote that good preachers, and I would say good Christians, should behave like bad kids. We ought to be mischievous enough to sneak in among dozing congregations and steal all their bottles of religion pills, and spirituality pills, and morality pills, and flush them all down the toilet.

Why? Because the church has drugged itself into believing that proper behavior is the ultimate pathway to God. We’re addicted to the certainty that, as bad as we might be, at least we’re not as bad as those other people over there.

There’s a reason reality TV is still such a favorite past time within and among the wider culture. We feel better about ourselves when we get to see other people behaving badly. It’s also why we’re quick to post photos of our perfect little families, even though they acted like animals while we were trying to get that perfect photo, so that everyone else will know, with certainty, that we have it all together.

But the sad truth is none of us know what we’re doing – some of us are better at pretending we know what we’re doing. But at the end of the day we’re all making it up along the way.

And yet, we can’t help ourselves from comparing ourselves to others in such a way that we are superior to their inferiority.

The crowds bring to Jesus their query; they want to know if people get punished for their sins – they want to know what it takes to be guilty.

And here’s the bottom line: if the God we worship punished us according to the sins we’ve already committed, the sins we’re currently committing, and even the sins we will commit in the future, then none of us would be around to worship in the first place.

Or, to put it another way: If every bad thing happens because God does it to punish us, then God isn’t worthy of our worship.

Over the centuries the church has been a place of guilt. Make em feel bad about their behavior, scare them about punishments in the hereafter, and they’ll show up in droves to hear about it all again next Sunday. And the same is true in our wider culture; we’re all keeping our little ledger books in our minds about who has done what to us.

But the strange new world of the Bible, the strange new world we talk about week after week, isn’t obsessed with guilt. No, if it’s obsessed with anything, it’s obsessed with forgiveness!

Christ died for us while we were yet sinners!

The Lamb of God has taken away the sins of the world!

What then, should we make of Jesus’ quip about repentance? “No, I tell you; but unless you repent you will die like them.”

Of course there should be repentance – a turning back, a return to the Lord. We’ve all wandered away from the Way. But repentance is supposed to be a joyful celebration, not a bargain chip we can cash in to get God to put up with us.

Repentance is a response to the goodness God has done, not a requirement to merit God’s goodness.

We can certainly feel guilty about our sins, and maybe we should. But feeling guilty about our sins doesn’t really do anything. In fact, the more we lob on guilt, the more likely we are to keep sinning because of our guilt.

The only thing we can ever really do about our sins, is admit them. It’s a great challenge to be able to see ourselves for who we really are, sinners in the hands of a loving God, and then take a courageous step in the direction of repentance. But if we ever muster up the gumption to do so, it will be because we live in the light of grace.

Grace works without requiring anything from us. No amount of self-help books, no number of piously repentant prayers, no perfect family, perfect job, perfect paycheck, perfect morality, perfect theology earns us anything.

Grace is not expensive. It’s not even cheap. It’s free.

And, according to the wondrous weirdness of the Lord, grace is like manure.

Or, perhaps we should call it holy fertilizer.

This is classic Jesus here. The crowds approach with their question and his answer to their question is a story, a parable.

A man has a vineyard and in the middle of the vineyard he planted a fig tree. But for three years it produced not a single fig. So one day the vineyard owner says to the gardener, “I can’t take it anymore. This fig tree is wasting my good soil. Cut it down.”

But the gardener looks at his employer and says, “Lord, let it be. Why not give it another year? I’ll spread some manure on it this afternoon and maybe next year it will have some fruit.”

Short and sweet as far as parables are concerned and yet, even in its simplicity there are a bunch of weird and notable details.

For instance, why does the vineyard owner plant a fig trees among a bunch of grapes? Do you think he was trying to develop a new, and perhaps bizarre, variety of wine? Or maybe he was going to start the first Fig Newton distribution service in Jerusalem?

Strange. But perhaps nothing is stranger than the gardener. This gardener speaks in defense of a speechless fig tree.

And what does the gardener says, “Lord, let it alone for a year. Let me give it some manure.”

At least, that’s what it sort of says in our pew bibles.

But in Greek, the gardener says, “KYRIE, APHES AUTEN.”

Literally, “Lord, forgive it.”

Lord, forgive it!

These might be some of the most striking for from the strange new world of the Bible both because they proclaim the forgiveness of the Lord for not reason at all, and because they help us to see how little we can.

There’s a reason that, when we nail Jesus to the cross, he declares, “Lord, forgive them for they do not know what we are doing.”

Lent is the strange and blessed time to admit, we have no idea what we’re doing. That we are in need of all the grace and manure we can get.

The cross with this we adorn the sanctuary, in all of its ugliness, is a sign and testament to Jesus becoming sin for us – how Jesus goes outside the boundaries of respectability for us, how he is damned to the dump because of us, and how he ultimately becomes the manure of grace for us.

It’s wild that Jesus has the gall to tell this story at all, and that the divine gardener offers to spread some holy fertilizer on the fig tree, on us.

Only in the foolishness of God could something so nasty, so dirty, so grossly inappropriate, becomes the means by which we become precisely who we are meant to be.

God’s grace gets dumped onto the fruitless fig trees of our lives and get co-mingled in the soil of our souls. It is messy and even bizarre, but without it we are nothing.

Jesus doesn’t give a flip whether we’ve got a fig on the tree or not. He only cares about forgiveness, a forgiveness we so desperately need because we have no idea what we’re doing.

For, if we knew what we were doing, we would’ve solved all the world problems by now. But we haven’t.

We are fruitless fig trees standing alone in the middle of God’s vineyard.

We are doing nothing, and we deserve nothing.

And yet (!) Jesus looks at our barren limbs, all of our fruitless works, our sin sick souls, and he says the three words we deserve not at all: “Lord, forgive them.”

On Friday afternoon, the aforementioned Vladimir Putin addressed the people of Russia during a rally that was celebrating the 8th anniversary of the annexation of Crimea. While Russian forces attacked Kyiv and blockaded civilians in other parts of Ukraine, Putin assured his people that Russia was forced into this war into to get the Ukrainian people out of their misery.

And then he said, “And this is where the words from the scriptures come to mind, ‘There is no greater love than if someone gives his soul for his friends.’”

That a world leader used Jesus’ words to justify violence and bloodshed is not unusual. It’s been done again and again throughout the centuries. Even here in the US, it is a familiar refrain whenever violence is on the table. Presidents Trump, Obama, Bush, and Clinton each used the quote at one point or another during their years in office.

But Jesus spoke those words before mounting the hard wood of the cross, not before going to war. Jesus laid down his life for his so-called friends who betrayed him, denied him, and abandoned him.

Jesus laid down his life for us.

And even with a crown of thorns adorning his head, and the cross over his shoulder, he still says, “Lord, forgive them.” Amen.

The River Of Life

This week on the Strangely Warmed podcast I speak with Wayne Dickert about the readings for the Third Sunday of Lent [C] (Isaiah 55.1-9, Psalm 63.1-8, 1 Corinthians 10.1-13, Luke 13.1-9). Wayner is the pastor of Bryson City UMC in Bryson City, NC. Our conversation covers a range of topics including the Nantahala River, joy, well-digging, recreation for re-creation, praise, church meetings, the ministry of restoration, idolatry, divine challenges, and holy fertilizer. If you would like to listen to the episode or subscribe to the podcast you can do so here: The River of Life

A Hermeneutic Of Inversion

Luke 13.31-35

At that very hour some Pharisees came and said to him, “Get away from here, for Herod wants to kill you.” He said to them, “Go and tell that fox for me, ‘Listen, I am casting out demons and performing cures today and tomorrow, and on the third day I finish my work. Yet today, tomorrow, and the next day I must be on my way, because it is impossible for a prophet to be killed outside of Jerusalem.’ Jerusalem, Jerusalem, the city that kills the prophets and stones those who are sent to it! How often have I desired to gather your children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings, and you were not willing! See, your house is left to you. And I tell you, you will not see me until the time comes when you say, ‘Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord.’”

Here we are, in worship, on the second Sunday of Lent, the season in which we are called to lament and repent. In the scriptures we continue to confront the condition of our condition and the tones of abject disappointment from the Lord as the cross grows clearer on the horizon.

Jesus, it seems, has grown frustrated with God’s people refusing to hear and heed the summons to return home.

Jesus, it seems, doesn’t have much time to spare for the ruler of the people because he has better things to do.

Jesus, it seems, sees few alternatives left other than the one we adorn our sanctuary with.

As Jesus’ ministry progresses, his lamentations increase just as the obstacles standing in his way increase.

For some reason the political and religious establishments are threatened by the poor and wandering rabbi with his messages of the Kingdom of God. They are threatened because talk of the meek inheriting the earth calls into question all of the power and prestige they have acquired.

Which makes the beginning of this scripture all the more strange. It is rather peculiar that the protective warning comes from the Pharisees who, up to this point in the Gospel, have been anything but concerned for Jesus’ wellbeing.

“Get out of here Jesus! Herod wants to kill you!”

And Jesus brushes the threat aside, “You tell that dirty rotten scoundrel that I’ve got work to do and places to be.”

During Lent the strange new world of the Bible keeps pointing to the cross. Just as the city of Jerusalem is on Jesus’ radar, so too it is for us. Jerusalem is the end.

And Jesus loves Jerusalem.

But it is a strange love.

Jesus describes his own love for the city as a mother hen who endeavors to wrap her wings around her helpless chicks.

And yet, Jerusalem has responded to God’s love and mercy with rebellion, with selfish ambition, with violence.

Jesus loves Jerusalem, but in the end his love for her will be the death of him.

And though it pains us to admit, the same is true for us – Jesus’ love for us, in the midst of our sin-sick souls, it such that it leads to his end.

There are some texts in the holy scriptures that seem to be nothing but trouble. Jesus, here, complains about the wandering hearts of Jerusalem, and how they fail to see the truth right in front of their faces. “See your house is left to you,” sounds like a threat from the Lord.

And yet, biblically speaking, whenever trouble is present, grace isn’t far away.

There is a divine inversion between what is good and bad, in and out, elect and reject.

Cain kills Abel and though God sets Cain to wander the earth for the rest of his days, he is also marked so that no one will bring the same fate that he brought to his brother.

Jacob swindles his brother Esau out of the inheritance and is confronted with an angel of the Lord who knocks his hip out of joint for the rest of the days shortly before he reconciles with his brother.

The favor and blessing of the Lord moves from Saul to David, and yet David commands the people of Israel to weep upon the death of their former king.

Whenever we encounter someone or a group who appears to be rejected by God, there is also some sense of election.

Grace, what we talk about all the time, isn’t so amazing unless there’s a reason for it. Put another way – the law of God is given in order that grace might be sought, and the grace of God is given in order that the law might be fulfilled.

We need rejection and election.

We need law and gospel.

Because that’s what life is like.

Karl Barth put it this way: “There is no light which does not also know darkness, no joy which does not have within it sorrow; but the converse is also true; no fear, no rage, which does not have, far or near, peace at its side. No laughter without tears, no weeping without laughter!”

John Wesley once said that every law contains a hidden promise.

Grace abounds.

In theological speak we might call it a hermeneutic of inversion – an understanding of things being flipped upside down.

In our passage, Herod wants to kill Jesus. And yet, at the same time, Jesus wants to save Herod.

Jerusalem will bring about Jesus’ death. And yet, at the same time, Jesus’ death will bring about Jerusalem’s salvation.

There is always more to the story than the story itself.

As I said last week, try as we might to move through the motions of Lent, at some point or another we will raise the question that Christians have been asking since the beginning: Who in the world is this Jesus we worship?

I mean, why is Jesus so upset about Jerusalem? Why does he lament what they have done and what they will do? In another part of scripture Jesus will command the disciples to brush the dust off their feet when they encounter a town that does not receive them. Why then does Jesus desire to gather the wayward city under the loving care of a mother hen’s wings?

Luke doesn’t tell us that Jesus wept over Jerusalem. But Matthew does.

And it’s rather revealing.

I did a funeral once for a man whose daughter had not one kind thing to say about her Dad. He was awful to her, he did truly despicable things. It was a miracle she even showed up for the service. And after we put him in the ground, she couldn’t stop crying. And when I asked her why she was crying all she could say was, “I don’t know. I don’t know.”

What good is it to lament the bad?

The target is on Jesus’ back, Herod wants him dead. And Jesus brushes away the threat of the Pharisees like it’s nothing.

And then he laments. Not over his life shortly coming to an end. But over Jerusalem, the killer of prophets.

He laments, he grieves, he weeps.

Lent, for us, is the season that provides a chance to lament. Whereas the world always wants to drag us from one thing to the next, Lent compels us to pause. It is a time to sit and grieve and acknowledge that all is not right with the world.

Nor with us.

We’ve behaved badly.

We have done things we ought not to have done.

We have left far too many things undone.

And yet, when it comes to lament, we are far more inclined to lament what happened to and with other people and other places.

It’s not hard for us to imagine Jesus’ lamenting over Jerusalem, because we can just as easily picture him weeping over Russia.

O Russia, O Russia. Look at what you’re doing to the people of Ukraine! You’re dropping bombs on maternity wards, displacing children from their parents, you’re destroying your own souls! O how I have longed to hold you within my lovingly embrace! Look at what you’ve become!

And yet, the inconvenient truth of the Gospel is that for as much as Jesus weeps over the state of other places and other people, Jesus also laments over us.

I wonder, how Jesus would react to us today? What would happen if Jesus looked down upon us from the top of Mill Mountain. Would Jesus cry?

Would he lament?

This is what prophets do: they call into question the powers and principalities regarding all their power and prestige. Prophets point right smack dab at our hearts and our desires and our sins and our shortcomings, they hold up a mirror to who we are, and they beg us to see the truth.

No wonder prophets live such short lives – no one likes being told the truth.

Will Willimon tells a story about how, when he was younger and living in Greenville, South Carolina, the whole place was abuzz with the news that Billy Graham was coming to town. There was going to be a revival. All the churches made plans for the special occasion and even the most ardently unChristian folks were still hoping to hear a word from the evangelist.

And, at Will’s church, they had a meeting about whether or not their church would participate in the revival. The pastor stood before the gathered body and made an impassioned plea – Graham is setting souls on fire, he is winning people for Christ, what a remarkable opportunity for our town, for our church.

And then someone else chimed in, “I’m not so sure pastor. Billy Graham seems charismatic and all, but did you hear that he lets black folk and white folk sit in the same section during his revivals? I don’t think we should be involved with someone who supports integration.”

And that’s all it took. The board voted right then and there to protect the church from Billy Graham’s sinful racial mixing.

After the meeting, Will says that he walked through the church to leave, but forgot something in the social hall so as he turned around in a hallway he heard the sound of sobbing. He crept down the hall. And there was the pastor’s door left slightly ajar. Will peeked inside and he saw his pastor, kneeling on the floor, holding his head in his hands, weeping.

There is something deeply profound and deeply troubling about the cross. It is, of course, the sign and marker of our delivery from Sin and Death. But, in the cross, we discover our reckless rebellion from the one who came to live, die, and live again, for us.

Jesus laments the city of Jerusalem. He weeps with the knowledge of his desire to gather the people in love and their constant refusal. And he declares the house is left to them.

To us.

When the house is left to us we like to decide who is in and who is out. We like to formulate our own rules about who is first and who is last, who is right and who is wrong, who is rejected and who is elected.

And so long as the house is left to us, it will not look like the kingdom of God.

Instead it will be a place that kills the prophets and stones those who are sent to it.

God in Christ desperately desires to gather us in, the lost and forsaken, like a hen gathers her brood under her wings. And we refuse.

So Jesus leaves the house to us.

But not forever.

“Truly I tell you,” Jesus says, “ you will not see me until the time comes when you say ‘Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord.’”

Those are the words sung by the crowds while waving their palm branches as Jesus enters Jerusalem on the back of a donkey.

Those are the same words that we, ourselves, will be singing in a few weeks.

You see, the Good News is that Jesus, in fact, does not abandon us to our own devices nor does Jesus leave us to our own houses. Instead, he arrives in the strangest of ways, banging on the doors of our own creation and says, through death and resurrection, this is my Father’s house.

Blessed is Jesus who comes in the name of the Lord because he is like us and so unlike us. He weeps and laments and loves precisely in our undeserving. He desires to gather us even when we push away. He still mounts the hard wood of the cross knowing full and well that, when push comes to shoves, our Hosannas will turn to Crucify in the blink of an eye. He still breaks forth from the tomb even though we put him there.

Jesus says to us, even today, look at who you are, and look at what you’re doing! Jesus still laments and cries, even for us.

Keeping up with the disruptive and demanding movements of a Holy and righteous God, it’s not for the faint of heart. It’s enough to make you cry. Amen.

Less Is More

This week on the Strangely Warmed podcast I speak with Chandler Ragland about the readings for the Second Sunday of Lent [C] (Genesis 15.1-12, 17-18, Psalm 27, Philippians 3.17-4.1, Luke 13.31-35). Chandler is the pastor of Black Mountain UMC in Black Mountain, NC. Our conversation covers a range of topics including strange new worlds, Encanto, covenants, righteousness, living in church, narrative preaching, memorizing scripture, waiting on the Lord, the Apostles’ Creed, Mississippi, and the status quo. If you would like to listen to the episode or subscribe to the podcast you can do so here: Less Is More

The Devil Is In The Details

Luke 4.1-13

Jesus, full of the Holy Spirit, returned from the Jordan and was led by the spirit in the wilderness, where for forty days he was tempted by the devil. He ate nothing at all during those days, and when they were over, he was famished. The devil said to him, “If you are the Son of God, command this stone to become a loaf of bread.” Jesus answered him, “It is written, ‘One does not live by bread alone.’” Then the devil led him up and showed him in an instant all the kingdoms of the world. And the devil said to him, “To you I will give their glory and all this authority; for it has been given over to me, and I give it to anyone I please. If you, then, will worship me, it will all be yours.” Jesus answered him, “It is written, ‘Worship the Lord your God, and serve only him.’” Then the devil took him to Jerusalem, and placed him on the pinnacle of the temple, saying to him, “If you are the Son of God, throw yourself down from here, for it is written, ‘He will command his angels concerning you, to protect you,’ and ‘On their hands they will bear you up, so that you will not dash your foot against a stone.’” Jesus answered him, “It is said, ‘Do not put the Lord your God to the test.’” When the devil had finished every test, he departed from him until an opportune time.

It is a long standing tradition in the church to begin the forty days of Lent with Jesus’ forty days in the wilderness. We, in a sense, mirror the journey Jesus faced with our own attempts at wrestling with temptation while abstaining from certain items, behaviors, and practices.

It’s not the easiest section of the church calendar.

The hymns are all a little too on the nose, the sermons call to question all of our wandering hearts, and even the scriptures reject our desire to look at anything but the cross.

We, then, can do lots of things as a church during this particular liturgical season, but at some point or another we will all raise the question we’ve had since the very beginning of the church: “Who, exactly, is this Jesus?”

It was just a few weeks ago that we were worshipping the baby born King in the manger, with little angels and shepherds wandering around the sanctuary. It’s easy to worship that Jesus because in infancy there isn’t much for us to come to grips with. We can confess the wonder of the incarnation, but we’re not entirely sure what that has to do with you or me.

But then, here in Lent, it’s like the Spirit wants to smack us over the head with the truth of the Truth incarnate.

And we start with Jesus’ temptations in the wilderness.

This vignette in the strange new world of the Bible tells us exactly who this Jesus is, and who he will be.

Oddly enough, it offers us a glimpse behind the curtain of the cosmos – it helps us see that the story of Christ will end just as it begins.

Jesus is baptized by his cousin John in the Jordan and then he is led by the spirit into the wilderness where for forty days he was tempted by the devil.

“Hey JC!” The devil begins, “If you are who you say you are, I’m gonna need to see some ID. No pockets in your robe? That’s fine. I’ll take your word for it, if you really are the Word. But, let me tell you, you look awful. I’m sure you’re hungry. Not a lot to eat out here in the wilderness. Why don’t you rustle up some bread from these stones. Who knows? That little parlor trick could come in handy down the road… what could be more holy than having mercy on the hungry and filling their bellies?”

And Jesus says, “It is written, we cannot and shall not live by bread alone.”

“So you know your scriptures!” The Devil says, “I’m impressed! And, frankly, I’m with you Son of Man. You can’t just give hungry people food for nothing. They’ll become dependent. No handouts in the Kingdom of God! But how about this? Would you like a little taste of power? And I mean, real power. Political power. Here’s the deal – I’ll give you the keys to the kingdoms here on earth, all of them. The only thing you have to do, and it’s really nothing when you think about it, I just need you to bow down and worship me.”

And Jesus says, “It is written, we shall only worship one God.”

“Okay, okay,” the Devil continues, “Don’t be such a buzzkill. So you won’t show compassion to the needy, even yourself, and you won’t go ahead and make the world a better place through political machinations. That’s fine with me. For what it’s worth, I can play the scripture game too, you know. So I’ll give you one more chance. Why don’t you leap from the top of the temple, give the people a sign of God’s power and might, for, doesn’t it say in the Psalms, ‘He will command his angels concerning you to guard you in all your ways. On their hands they will bear you up, so that you will not dash your foot against a stone.’ Just think about the kind of faith people will finally have if you show them one big miracle!”

And Jesus says, “It is written, you shall not put the Lord you God to the test.”

And then the devil leaves only to return at an opportune time.

That’s rather an ominous ending to a passage of scripture. But, no spoilers. Let stick with what we’ve got for now.

As I said at the beginning, we often use this story to give a little encouragement in resisting our own temptations. This is the time for someone like me to make a big pitch to people like you about whatever bad habit you need to drop. The time has come to shape up or ship out.

And, clearly, we’ve got plenty to work on. There are far too many people who fall asleep hungry at night, far too many children to have no bright hope for tomorrow, far too many communities that are falling prey to the devastating powers of loneliness.

But, if that’s all this story is supposed to do, if it merely exists as a weapon to wield against sleepy and dozing congregations about being better, then Jesus certainly could’ve been a little clear about what we should or shouldn’t be going.

Put another way: If Jesus’ temptations are really about our temptations, then it would’ve been better for him to have more lines in this passage than the devil.

Scripture is always primarily about God and only secondarily about us.

But we are vain and selfish little creatures and we assume everything is always about us, and only ever about us.

Jesus’ temptations are exactly that – Jesus’ temptations.

This isn’t a story about how we deal with our own temptations. It’s actually a story about how Jesus deals with the world – how Jesus deals with us.

Notice: the things the devil offers to the Lord, they’re all objectively good things – bread, political power, miracles.

And yet, Jesus refused them. And he even used scripture to defend his refusals!

Perhaps if the devil offered Jesus an unending buffet at the golden corral, or the nuclear codes, or David Copperfield’s assortment of illusions, we could sympathize with Jesus’ dismissals. But the devil offered Jesus possibilities for transformation and Jesus said, “No, thank you.”

But here’s the real kicker, the truly wild part of this story: by the end of the Gospel Jesus will, in fact, do all of the things that the devil suggests.

Instead of turning some rocks into a nice loaf of sourdough, Jesus will feed the 5,000 with nothing more than a few slices of day old bread a handful of fresh fish.

Instead of getting caught up in all the political procedures to Make Jerusalem Great Again, Jesus reigns from the arms of the cross and eventually ascends to the right hand of the father as King of kings and Lord of lords.

Instead of pulling off a primetime Law Vegas magic special, Jesus dies, and refuses to stay dead.

For a long, long, time we’ve understood Jesus and the Devil to be figures on opposite ends of the spectrum – one good and the other bad. It even slips into out culture whenever you see a figure with an angel whispering in one ear and a red figure with a bifurcated tail whispering in the other.

And yet, at least according to this moment in scripture, the difference between the devil and Jesus isn’t the temptations themselves, but in the methods upon which those acts of power come to fruition.

And, though it might pain us to admit, the devil has some pretty decent suggestions for the Messiah – Why starve yourself Lord, when you can easily set a meal here in the wilderness? Why let these fools destroy themselves when I can give you control over everything and everyone? Why let the world continue in fear and doubt when you can prove your worth right now?

The devil, frighteningly, sounds a lot like, well, us. The devil’s ideas are some that we regularly discuss and champion.

What our community needs is another food pantry! What we need to do is make sure that we have Christians running for political offices! If only God would show us a miracle, then everyone would finally get in line and the world will finally be a better place.

But Jesus, for as much as Jesus is like us, Jesus is completely unlike us. For, in his non-answer answers he declares to the devil, and therefore to all of us, that power as we understand it doesn’t actually transform much of anything.

We can create a feeding program, but sooner or later we will introduce requirements for those who receive the food.

We can get Christians elected into the government, but at some point they will be more concerned with maintaining their power than pointing to the one from whom all things move and have their being.

We can witness miracle after miracle after miracle, but we will never be quite satisfied with what we receive.

We’ve convinced ourselves, since that fateful day with a certain fruit in a certain tree, that it’s up to us to make things come out right in the end. That, by amassing power, we can make the world a better place.

In the early days of the church, we got so cozy with the powers and the principalities that individuals were forced to be baptized in order to becomes citizens in the empire.

In the Middle Ages, the church required more and more of the resources of God’s people in order to get their loved ones out of purgatory all while cathedrals got bigger, as did the waistlines of the clergy.

And even today, our lust for power (political, theological, economic), has led to violence, familiar strife, and ecclesial schisms.

We believe, more than anything else, that if we just had a little more control, if we just won one more debate, if we could just get everyone else to be like us, that it would finally turn out for the best.

But it never does.

If we could’ve fixed the world with our goodness, we would’ve done it by now.

Or, conversely, some of the most horrific moments of history were done in the name of progress.

The devil wants to give Jesus a short cut straight to the ends that Jesus will, inevitably, bring about in his own life, death, and resurrection.

The devil wants Jesus to do what we want Jesus to do.

Or, perhaps better put: The devil wants Jesus to do what WE want to do.

But here’s the Good News, the really Good News, Jesus rejects the temptations of the devil, and our own, and instead does for us what we would not, and could not, do for ourselves.

Even at the very end, with his arms stretched out not he cross, we still tempt the Lord just as the devil did: “If you really are who you say you are, save yourself!”

And, at the end, Jesus doesn’t bother with quotes from the scriptures, nor does he provide us with a plan on how to make the world a better place, he simply dies.

Instead of saving himself, Jesus saves us. Amen.

Beauty In Brokenness

Psalm 51.1-17

Have mercy on me, O God, according to your steadfast love; according to your abundant mercy blot out my transgressions. Wash me thoroughly from my iniquity, and cleanse me from my sin. For I know my transgressions, and my sin is ever before me. Against you, you alone, have I sinned, and done what is evil in your sight, so that you are justified in your sentence and blameless when you pass judgment. Indeed, I was born guilty, a sinner when my mother conceived me. You desire truth in the inward being; therefore teach me wisdom in my secret heart. Purge my with hyssop, and I shall be clean; wash me, and I shall be whiter than snow. Let me hear joy and gladness; let the bones that you have crushed rejoice. Hide your face from my sins, and blot out all my iniquities. Create in me a clean heart, O God, and put a new and right spirit within me. Do not cast me away from your presence, and do not take your holy spirit from me. Restore to me the joy of your salvation, and sustain in me a willing spirit. Then I will teach transgressors your ways, and sinners will return to you. Deliver me from bloodshed, O God, O God of my salvation, and my tongue will sing aloud of your deliverance. O Lord, open my lips, and my mouth will declare your praise. For you have no delight in sacrifice; if I were to give a burnt offering, you would not be pleased. The sacrifice acceptable to God is a broken spirit; a broken and contrite heart, O God, you will not despise.

In the strange new world of the Bible the greatest triumph, the pinnacle of all moments, is Jesus’ resurrection from the dead. Easter. But Easter is not the “happy ending” of a fairytale. It’s not, “despite all the effort of the powers and the principalities, everyone lives happily ever after.”

There’s no resurrection without crucifixion.

But that’s also why there are far more people in church on Easter than on Ash Wednesday and Good Friday.

Easter, for all of its wonder and all of its joy, is only the beginning of a new reality in which the entry point is, in fact, suffering.

Contrary to the cliche aphorisms of the so-called property gospel – if you pray hard enough, God will make you healthy and wealth – struggle is deeply embedded in the faith. It’s why Jesus warns about the cost of discipleship, constantly. It’s why Paul writes about suffering, constantly.

Struggles are present in the life of faith because, when push comes to shove, we usually look out for ourselves at the expense of our neighbors. Paul puts it this way: None of us is righteous. No, not one.

We simply can’t keep the promises we make, let alone the promises that God commanded us to keep. It doesn’t take much of a glance on social media or on the news to see, example after examples, of our wanton disregard for ourselves and even for ourselves.

The old prayer book refers to us, even the do gooders who come to an Ash Wednesday service, as miserable offenders.

And yet (!), God remains steadfast with us in the midst of our inability to be good.

That’s one of the most profound miracles of the strange new world of the Bible, and it is a miracle. That ragtag group of would be followers we call the apostles, who betray, abandon, and deny Jesus, they fail miserably and it is to them that the risen Jesus returns in the resurrection.

They were transfigured by the Transfigured One, and their journey of faith began in failure.

And so it is with us, even today. It is through our brokenness, our shattered souls, that God picks up the pieces to make something new – something even more beautiful than who were were prior to the recognition of our brokenness.

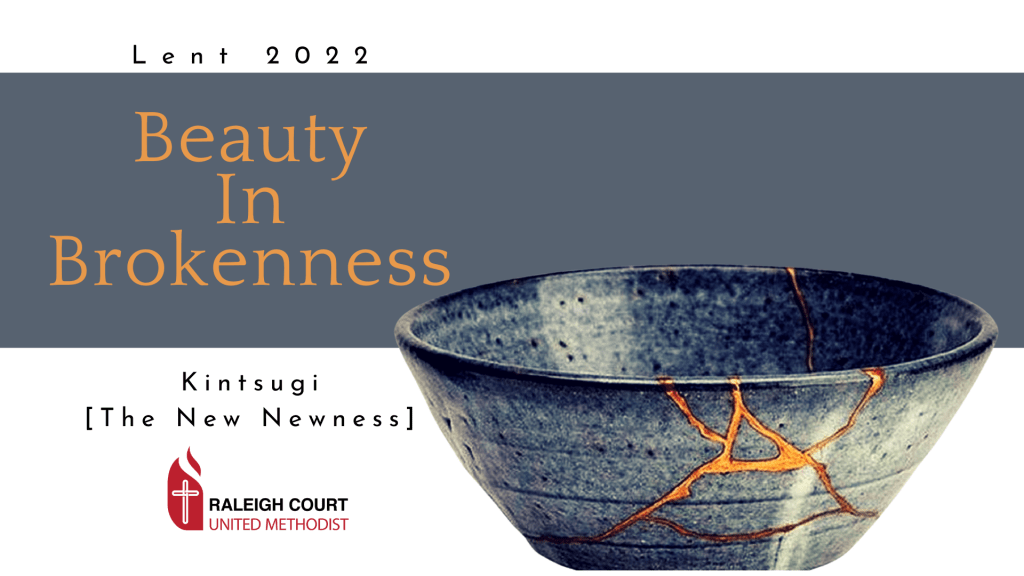

There is an ancient Japanese art form that will be shaping our Lenten observance this year at the church – Kintsugi. The story goes that, centuries ago, a disagreement broke out among an emperor and one of his servants which led to a tea pot being smashed into pieces. The emperor threatened to punish the servant but an artisan intervened and promised to make something of the nothing.

A gold binding agent was used by the artist to restore the broken vessel, and in so doing the artist brought to a new newness.

On the front of your bulletins you can see an example of this art form that was made with a broken cross – the gold ribbon brings the cross back together and it becomes more than it was prior to its cracks and fissures.

Like the Kintsugi master, Jesus renders us into a new newness. Jesus comes not to fix us, but to admire us in our potential and to help us recognize beauty even in, and precisely because of, our brokenness.

In church speak we call it redemption.

Psalm 51 had marked the season of Lent for as long as Christians have observed this particular season. It is a penitential psalm – a psalm that expresses sorrow for sin.

And yet, the psalm does not begin with a confession of sin – it begins with a request for forgiveness: “Have mercy on me, O God, according to your steadfast love; according to your abundant mercy, blot out my transgressions.”

That might not seem like much of a distinction, but it implies that the psalmist knows they have something worth confessing and that if the psalmist is to be helped at all then the sins must be taken away completely but someone else.

It means the psalmist really knows the condition of their, and our, condition. We all do things we know we shouldn’t do, and we all avoid doing things we know we should do.

Some us are are pretty good at pushing that all aside and rationalizing the things we do or leave undone. But at some point or another the guilt begins to trickle in and we lay awake at night unable to do much of anything under the knowledge of who we really are.

But the psalmist sees it all quite differently.

Somehow, the psalmist knows that forgiveness has come even before the sin occurred.

The psalmist knows that God is the God of mercy.

For us, people entering the season of Lent, we are compelled to proclaim the truth that we are justified not after we confess our sins, but right smack dab in the middle of them. At the right time Christ died for the ungodly, God proves God’s love toward us that, while we were yet sinners, Christ died for us. There is therefore now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus, which includes everyone since Jesus has taken all upon himself in and on the cross.

The challenge then, for us, isn’t about whether or not God will forgive us.

The challenge is whether or not we can confess the condition of our condition.

That’s why Ash Wednesday is so important and so difficult. It is a time set apart to begin turning back to God who first turned toward us. It is a remarkable opportunity to reflect on what we’re doing with our lives right now and how those lives resonate with the One who makes something beautiful out of something broken.

Therefore, Ash Wednesday inaugurates the season of honesty:

We are dust and to dust we shall return.

We are broken and are in need of the divine potter to do for us that which we cannot do for ourselves.

Judgment comes first to the household of God, so wrote Peter in an epistle to the early church. We, then, don’t exist to show how wrong the world is in all its trespassed, but instead we exist to confess that we know the truth of who we are all while knowing what the Truth incarnate was, and is, willing to do for us.

We can’t fix ourselves. In any other place and in an other institution and around any other people that is unmitigated bad news. But here, in the church, it’s nothing but Good News. It’s good news because nobody, not the devil, not the world, not even ourselves can take us away from the Love that refuses to let us go.

Even the worst stinker in the world is someone for whom Christ died.

Even the most broken piece of pottery can be made into something new by the divine potter.

I wonder, this Lent, what kind of church we would become if we simply allowed broken people to gather, and did not try to fix them, but simply to love them and behold them, contemplating the shapes that broken pieces can inspire?

I wonder, this Lent, what might happen if we truly confessed who we are all while knowing whose we are?

I wonder, this Lent, what kind of new newness we might discover through the One who comes to make all things new?

You and me, we’re all dust, and to dust we shall return. But dust is not the end. Amen.

Words About The Word

This week on the Strangely Warmed podcast I speak with Chandler Ragland about the readings for the First Sunday of Lent [C] (Deuteronomy 26.1-11, Psalm 91.1-2, 9-16, Romans 10.8b-13, Luke 4.1-13). Chandler is the pastor of Black Mountain UMC in Black Mountain, NC. Our conversation covers a range of topics including Lenten observances, first fruits, Karl Barth on time, doom and gloom, institutional identities, rocking climbing, angelology, imaging salvation, preaching anxieties, Twitter, and temptation. If you would like to listen to the episode or subscribe to the podcast you can do so here: Words About The Word