Isaiah 35.1-10

The wilderness and the dry land shall be glad, the desert shall rejoice and blossom; like the crocus it shall blossom abundantly, and rejoice with joy and singing. The glory of Lebanon shall be given to it, the majesty of Carmel and Sharon. They shall see the glory of the Lord, the majesty of our God. Strengthen the weak hands, and make firm the feeble knees. Say to those who are of a fearful heart, “Be strong, do not fear! Here is your God. He will come with vengeance, with terrible recompense. He will come and save you.” Then the eyes of the blind shall be opened, and the ears of the deaf unstopped; then the lame shall leap like a deer, and the tongue of the speechless sing for joy. For waters shall break forth in the wilderness, and streams in the desert; the burning sand shall become a pool, and the thirsty ground springs of water; the haunt of jackals shall become a swamp, the grass shall become reeds and rushes. A highway shall be there, and it shall be called the Holy Way; the unclean shall not travel on it, but it shall be for God’s people; no traveler, not even fools, shall go astray. No lion shall be there, nor shall any ravenous beast come up on it; they shall not be found there, but the redeemed shall walk there. And the ransomed of the Lord shall return, and come to Zion with singing; everlasting joy shall be upon their heads; they shall obtain joy and gladness, and sorrow and sighing shall flee away.

It’s a thing that takes place, more often than I would like. Someone wanders into my office and before long they say, “Why did this happen?”

Why do Russian forces continue to attack civilians in Ukraine, killing innocents daily?

Why did my cells mutate into a cancer that is trying to kill me?

Why would my husband hurt me so much?

Those are worthy Advent questions.

Why?

We’ve got the lights and the cocoa, some of us already have presents wrapped under the tree and are putting together the menu for when the relatives arrive. We’ve got all this other stuff going on and yet we know that not all is as it ought to be.

Even if you feel like you’ve got it all figured out, spend one minute watching the nightly news and you are likely to be bombarded with stories and images of all that is wrong with this world.

Why is this world so broken? What can we, the church, say about all the sorrow, the waste, the vengefulness that populates the evening news and keeps us awake at night?

John the Baptist had the same questions. Sure, he prepared the way out in the wilderness, he called for the baptism for the repentance of sins, he talked about the One to follow. But his talk was incendiary, downright revolutionary, according to the powers and the principalities, and it got him locked up.

And from prison John starts to wonder about his cousin Jesus. “He sure seems like the Messiah. He walks like the Messiah, he talks like the Messiah. And yet, where is all the grand and Messianic stuff to inaugurate this time? Why isn’t Jesus more like me?”

So John sends word by way of his disciples, “Hey cuz, are you the real deal? Or are we to wait for another?”

And Jesus, in typical Jesus fashion, responds in his own weird way. He says to his own disciples, “Tell my cousin what you have seen and heard: the blind see, the lame walk, the deaf hear, the poor have good news.”

Jesus, notably, quotes the prophet Isaiah, the very text we read this morning. A text from 700 years before Jesus arrived on the scene and John got locked up.

Jesus is saying to John, by way of his disciples, that he is, indeed, the One to come and the time has already arrived. “The kingdom is breaking in, J the B, you’ve set your sights too low. You want to defeat the empire called Rome. Well, I’ve come to vanquish the empire of sin and death. It’s already begun because I am here. I am the kingdom in the flesh.”

This proclamation, this promise, of the blind seeing, the lame walking, the deaf hearing, it’s a recurring theme in scripture. Isaiah has a glimpse of it. Jesus preaches on it in his first sermon. The disciples witness it.

It’s the ministry of divine inversion. It’s no different than Isaiah talking about streams in the desert and the hills being brought low. The work of the Lord makes a way where there is no way.

And yet, Jesus’ answer to his cousin, his pointing to the work made manifest in the flesh, is somewhat incomplete. The rugged Advent faith compels us to admit that something is amiss. Yes, Jesus did heal a few blind people, but only a few. Yes, he did feed the hungry and cure the sick. But how many?

The signs of the in-breaking kingdom, the work of the Lord then and now, is left undone.

That’s the strange tension of Advent – of living between the already but not yet, of being stuck in the time being.

The kingdom of God is mysterious.

Mysteries are fundamentally unsatisfying. We are not content to rest under the shadow of the unexplained. So we bring our expectations and questions to Jesus over and over again, not unlike John did from behind bars, and Jesus, more often than not, gives us mystery.

Preachers like me are always looking for stories, these moments of impact where the Gospel hits us in the heart. And sometimes the stories arrive from unexpected places.

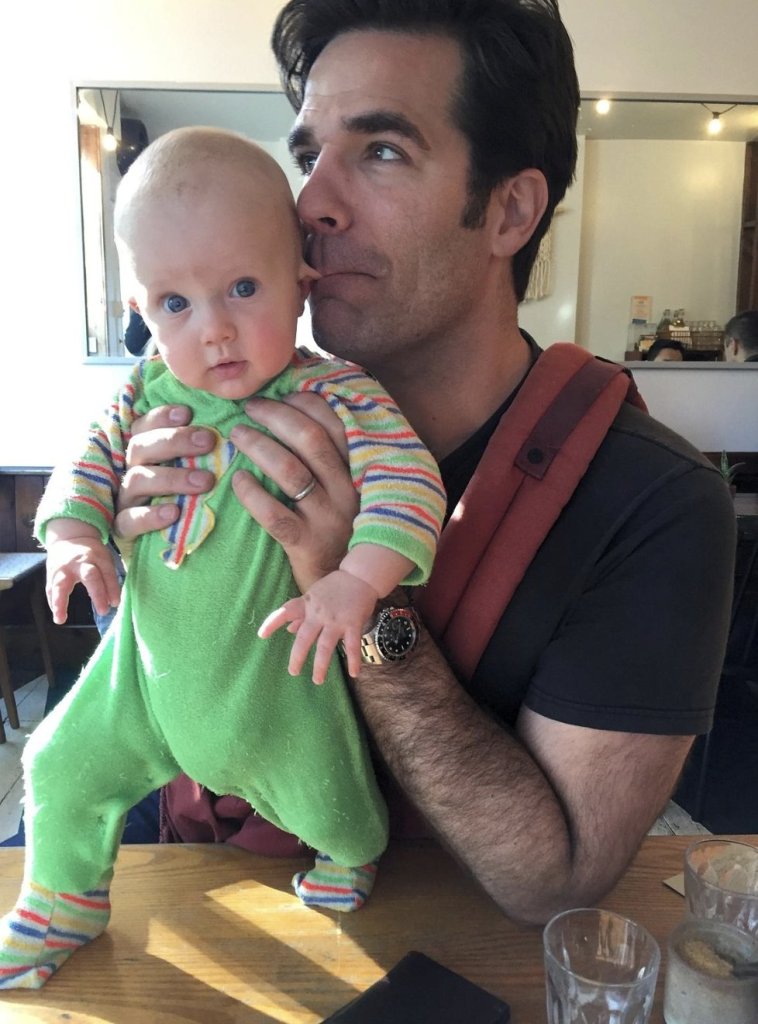

Rob Delaney is an actor and comedian, known for bit parts in various films and a short-lived British series titled Catastrophe. He’s made a career out of making people laugh. And this week Delaney has been making the day-time and late-night tv circuit promoting his new memoir titled A Heart That Works. The title comes from a song lyric: A heart that hurts, is a heart that works.

That’s a strange title for a memoir from a comedian.

The book tells of Delaney’s experience of profound loss and pain. His third son, named Henry, around the time of this 1st birthday got sick. Very sick. It took a long time to figure out what was going on, and they eventually discovered that Henry had a brain tumor. He had extremely invasive surgery and chemotherapy that left him disabled. After a year and a half of time in and out of the hospital, the tumor returned and he died.

When asked about why Delaney chose to write the memoir, again and again he has responded, “I wanted to return to humanity, and I didn’t know how other than to write about it.”

And so, day after day, Delaney has sat down for interview after interview, being forced to relive something that no one should ever have to experience.

And this week, while sitting down for a conversation on CBS, Delaney interrupted the program and looked across the table to Gayle King and said, “Gayle, you came up to me this morning before we came out here in front of the cameras and you hugged me, and asked me genuine questions, and you cried. You offered me a beautiful and human response. And I want you to know it’s the best thing that’s happened to me in days.”

Gayle King, unflappable Gayle King, stared back at him with this bewildered look and said, “How can that be the best thing?”

And Delaney said, “You had a genuine response. I don’t want people to ask these perfunctory questions, and say ‘Oh, your grief,’ and then move on as if nothing happened. I want people to cry. My boy is dead. I won’t hold him again. I hold him in my heart and I think about him all the time. But you had a response like that and that was like water to me in the desert. It was beautiful.”

“It was like water in the desert.” The prophet Isaiah speaking through a comedian, on CBS.

And what makes that interaction even all the more extraordinary, is that Delaney is an atheist. Except, later in the week, this time while on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, Delaney was pushed by the host to reflect on what his grief has done to him and he said, “It’s a big problem for me that, as an atheist, my faith organ has been growing in the years after my son’s death.”

Water in the desert.

We tend to treat grief like a plague. We stay away from it. We close our doors to it. And if we have it, we do whatever we can to get rid of it. But you know, grief is actually good.

Grief is just unexpressed love. Grief is how love perseveres.

It’s Advent. It’s that time of year when we pull our the greenery and we sing the songs and we light the candles. Today, the pink candle is lit. It’s Gaudete Sunday, rejoice, the Sunday for joy, pink is the liturgical color for joy. It’s a bit odd, I think, that we keep lighting this pink candle year after year.

Because, how can we be joyful in a time like this?

How can someone like Rob Delaney be joyful?

Grief is like a hole that cannot be filled no matter how hard we try. No number of presents can make up for the pain that we too often encounter in this life. And yet we are bold to light that candle.

We light it not as a denial of the harsh realities of life, but because joy is something that is done to us.

Joy is what happens when we dare to trust the Lord to do for us that which we cannot do on our own.

Joy is what happens when we are able to look at what we have, and had, and know that all of it, the good and the bad, came as a gift. Something rather than nothing.

Joy is what happens whenever we encounter water in the midst of the deserts of our grief.

When we weep with others, or even rejoice with others, does it fix everything? Does it set everything right?

What good is a cup of water in the desert? It doesn’t get rid of the desert!

And yet, the mystery of God’s activity in the world is that even the tiniest signs of faithfulness and love and mercy and hope are the pointers to the glory that will come when the Lord comes to make all things new.

The hope of Advent, of all time really, is possible precisely because what we have now is not all there is. We have these lights, and prayers, and songs because the point us to the greater reality that beats upon our lives ever day: God loves us, and this is not the end.

I don’t know if this was the sermon you expected to hear this morning. I can assure you, this is not the sermon I thought I would be preaching at the beginning of the week. And yet, we worship the God of the unexpected. The God who provides water in the desert. The God who lifts the valleys up and brings the mountains low. The God who takes on flesh to dwell among us. The God who mounts the hard wood of the cross for us. The God who breaks forth from the empty tomb and returns to us.

The proclamation of the gospel is that God comes to us in the brokenness of our health, in the shipwreck of our family lives, in the loss of all possible peace of mind, even in the thick of our sins. God, oddly, saves us in our disasters, not from them.

Isaiah says the redeemed of the Lord shall return, and come to Zion with singing; everlasting joy shall be upon their heads; they shall obtain joy and gladness, and sorrow and sighing shall flee away.

That is God’s promise to us. And until it comes to fruition, the least and the best we can do, is be water in the desert for others. Amen.